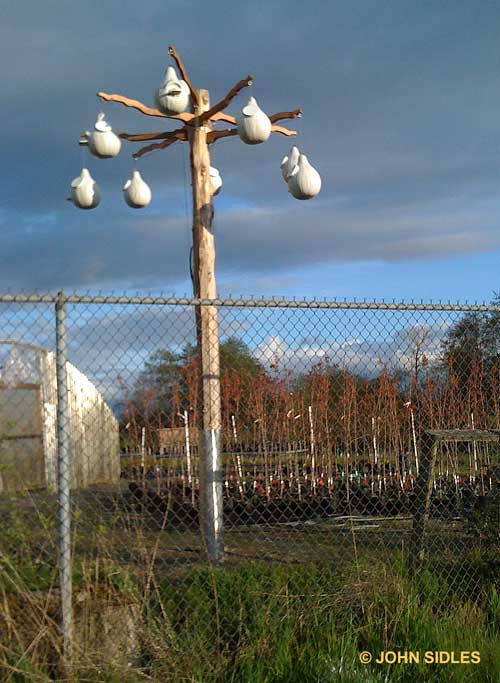

Yesterday the UW Botanic Gardens staff installed some new condominiums west of the greenhouses near the Center for Urban Horticulture (CUH). Oh, not for people, but for Purple Martins.

Male Purple Martin in flight.

Purple Martins, you see, are our largest swallows, and they have been in decline for a long time. They nest in holes, and they like to live together in a colony. Natural habitat that suits them has vanished from our area, and for a while, so did the martins.

Then about ten years ago, one man — a water quality expert and biologist named Kevin Li — began to install houses for Purple Martins all over Puget Sound. He put up natural gourds for the birds among the pilings near Ray’s Café in Shilshole Bay, at Fort Lawton, in Edmonds, and many other places. Birders began to see Purple Martins again in the skies over Seattle.

Before he died in a diving accident in 2006, Kevin tried twice to install gourds at the Fill. Both times, the gourds were stolen by vandals. After Kevin’s death, no one tried again.

Until now. A couple months ago, Friends of Yesler Swamp were brainstorming about how to improve bird habitat in the swamp (the easternmost section of the Fill). Kevin’s efforts were mentioned, and everyone immediately realized: Purple Martins belong here.

Within days, the word went out to the birding community: We need money to buy Purple Martin gourds. Birders responded immediately, donating enough to buy eight state-of-the-art gourds. These gourds are specially designed for Purple Martins. They are molded from real gourds but made of UV-resistant white plastic to resist mold and reflect the hot sun, so baby birds can stay cool inside. The gourds have a little porch for the birds to perch on, and an entrance hole that is ridged so starlings and other pests cannot enter to take over the nest.

In the course of our brainstorming, David Zuckerman of UW Botanic Gardens remembered seeing an unused cedar log at the Arboretum which could be repurposed to make a perfect stand to hold the gourds. Jerry Gettel of the Friends offered to assemble the gourds when they arrived from the manufacturer, and to make a cedar arm for each one, with cordage to raise and lower the gourds so they can be cleaned when nesting season is over.

Two weeks later, a small group of staffers gathered near the greenhouses to dig a post hole by hand. When it was deep enough, they hefted the 13-foot post with sheer muscle power and lowered it into the hole. Then they hung up the gourds carefully, one by one. We were all thrilled when the pole went up and the gourds started swinging in the breeze. Inside each gourd are clean cedar chips, waiting for a martin passerby to take note and move in.

Our new condos.

All together, we have created a work of art that will, we hope, bring purple martins back to the Fill. No one of us could have achieved this alone. Like everything else at the Fill, this project worked because we all helped, because we all respect nature, and most of all, because we try as best we can to balance the needs of people and wildlife.

Purple Martin mom feeding her babies.

As human beings, we each have within us the power to create much of our own environment, at least the cultural parts. What we choose to create is up to us — as individuals, but also as people working together. I hope when we each make our choices about how to act in both our natural and cultural worlds, that we choose to better our environment and bring out the best in each other.

FUN FACTS ABOUT PURPLE MARTINS

• They catch and eat insects on the fly.

• Native Americans have provided nesting gourds for purple martins for centuries.

• Eastern purple martins like apartment-style houses best; western martins prefer gourds.

• Purple martins like to be around people. They are very gregarious.

• Martins are noisy birds with several different songs and calls. Males have a special song they sing at dawn.

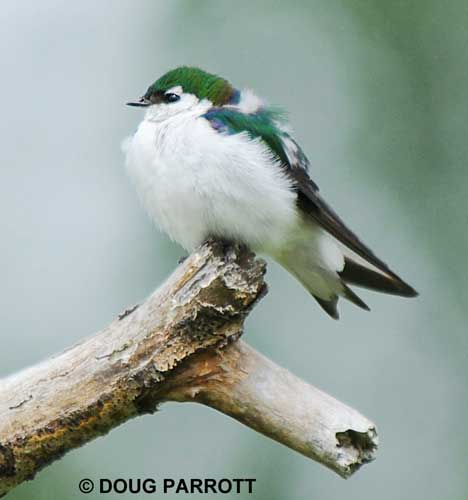

• Males look black in dull light and deep, iridescent purple in bright sunlight.

• Females can lay up to five eggs in one gourd.

• Once eggs are laid, they take only a couple of weeks to hatch. Babies are ready to fly a month after that.

• Purple Martins spend the winter in the Amazon Basin.

• Before they migrate, they get together in large groups and then fly south together.

• Thousands of martins used to sit on the powerlines around Green Lake before their population crashed.